Hurricanes

Hurricanes are large, swirling storms. They produce winds of 119 kilometers per hour (74 mph) or higher. That's faster than a cheetah, the fastest animal on land. Winds from a hurricane can damage buildings and trees. Hurricanes form over warm ocean waters. Sometimes they strike land. When a hurricane reaches land, it pushes a wall of ocean water ashore. This wall of water is called a storm surge. Heavy rain and storm surge from a hurricane can cause flooding. Once a hurricane forms, weather forecasters predict its path. They also predict how strong it will get. This information helps people get ready for the storm. There are five types, or categories, of hurricanes. The scale of categories is called the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. The categories are based on wind speed.

- Category 1: Winds 119-153 km/hr (74-95 mph) - faster than a cheetah

- Category 2: Winds 154-177 km/hr (96-110 mph) - as fast or faster than a baseball pitcher's fastball

- Category 3: Winds 178-208 km/hr (111-129 mph) - similar, or close, to the serving speed of many professional tennis players

- Category 4: Winds 209-251 km/hr (130-156 mph) - faster than the world's fastest rollercoaster

- Category 5: Winds more than 252 km/hr (157 mph) - similar, or close, to the speed of some high-speed trains

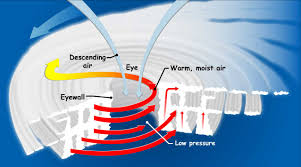

Eye: The eye is the "hole" at the center of the storm. Winds are light in this area. Skies are partly cloudy, and sometimes even clear. Eye wall: The eye wall is a ring of thunderstorms. These storms swirl around the eye. The wall is where winds are strongest and rain is heaviest. Rain bands: Bands of clouds and rain go far out from a hurricane's eye wall. These bands stretch for hundreds of miles. They contain thunderstorms and sometimes tornadoes.

How Does a Storm Become a Hurricane?

A hurricane starts out as a tropical disturbance. This is an area over warm ocean waters where rain clouds are building. A tropical disturbance sometimes grows into a tropical depression. This is an area of rotating thunderstorms with winds of 62 km/hr (38 mph) or less. A tropical depression becomes a tropical storm if its winds reach 63 km/hr (39 mph). A tropical storm becomes a hurricane if its winds reach 119 km/hr (74 mph).

What Makes Hurricanes Form?

Scientists don't know exactly why or how a hurricane forms. But they do know that two main ingredients are needed. One ingredient is warm water. Warm ocean waters provide the energy a storm needs to become a hurricane. Usually, the surface water temperature must be 26 degrees Celsius (79 degrees Fahrenheit) or higher for a hurricane to form. The other ingredient is winds that don't change much in speed or direction as they go up in the sky. Winds that change a lot with height can rip storms apart.

How Are Hurricanes Named?

There can be more than one hurricane at a time. This is one reason hurricanes are named. Names make it easier to keep track of and talk about storms. A storm is given a name if it becomes a tropical storm. That name stays with the storm if it goes on to become a hurricane. (Tropical disturbances and depressions don't have names.) Each year, tropical storms are named in alphabetical order. The names come from a list of names for that year. There are six lists of names. Lists are reused every six years. If a storm does a lot of damage, its name is sometimes taken off the list. It is then replaced by a new name that starts with the same letter.

How Does NASA Study Hurricanes?

NASA satellites take pictures of hurricanes from space. These pictures are shown on TV. They are also shown on the Internet. Some satellite instruments measure cloud and ocean temperatures. Others measure the height of clouds and how fast rain is falling. Still others measure the speed and direction of winds. NASA scientists use data, or facts, from satellites and other sources to learn more about hurricanes. The data helps them understand how hurricanes form and get stronger. The data also helps forecasters predict the path and strength of hurricanes. Did you know that dust storms from Africa might affect hurricanes? Two NASA satellites have a tool that helps scientists study how dust impacts hurricanes. NASA also flies airplanes into and above hurricanes. The instruments onboard gather details about the storm. Some parts of a hurricane are too dangerous for people to fly into. To study these parts, NASA uses airplanes that operate without people. NASA also carries out special projects to learn more about hurricanes. These projects use a mix of instruments on satellites, on aircraft and on the ground.

Hurricane Ike was a powerful tropical cyclone that swept through portions of the Greater Antilles and Northern America in September 2008, wreaking havoc on infrastructure and agriculture, particularly in Cuba and Texas. In these places, Ike remains the costliest tropical cyclone on record. Other locations were also seriously affected by Ike, which was ultimately the third-costliest of any Atlantic hurricane and resulted in $37.5 billion in damages, with hurricanes Sandy and Katrina causing more damage, at $75 and 108 billion, respectively. Ike developed from a tropical wave west of Cape Verde on September 1[nb 1] and strengthened to a peak intensity as a Category 4 hurricane over the open waters of the central Atlantic on September 4 as it tracked westward. Several fluctuations in strength occurred before Ike made landfall on eastern Cuba on September 8. The hurricane weakened prior to continuing into the Gulf of Mexico, but increased its intensity by the time of its final landfall on Galveston, Texas on September 13. The remnants of Ike continued to track across the United States and into Canada, causing considerable damage inland, before dissipating two days later. Ike was blamed for at least 195 deaths. Of these deaths, 74 were in Haiti, which was already trying to recover from the impact of three storms (Fay, Gustav, and Hanna) which had made landfall that same year. Seven people were killed in Cuba from Ike.[1] In the United States, 113 people were reported killed, directly or indirectly, and 16 were still missing as of August 2011.[2] Due to its immense size, Ike caused devastation from the Louisiana coastline all the way to the Kenedy County region near Corpus Christi, Texas.[3] In addition, Ike caused flooding and significant damage along the Mississippi coastline and the Florida Panhandle[4] Damages from Ike in U.S. coastal and inland areas are estimated at $29.5 billion (2008 USD),[2] with additional damage of $7.3 billion in Cuba (the costliest storm ever in that country), $200 million in the Bahamas, and $500 million in the Turks and Caicos, amounting to a total of at least $37.5 billion in damage. Ike is now the third-costliest Atlantic hurricane of all time, only surpassed by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and later by Hurricane Sandy in 2012.[5] The search-and-rescue operation after Ike is the largest search-and-rescue operation in Texas history.[6] Ike was the third major hurricane of the 2008 Atlantic hurricane season.